Thomas Sills (1914-2000)

Red Dream

1953

oil on canvas

49 x 44 inches

signed

labels with title and date verso

The title and correct size appear in an exhibition listing:

The Circle, Staten Island Museum, Feb-April 1963

This work may have possibly been exhibited at Sills' show at Betty Parson in 1957

Provenance: private collection, Houston, TX

The Amarillo Connection

Thomas Sills and wife, mosaicist Jeanne Reynal.

George “Dord” Fitz (1914-1989) was an artist, teacher, and gallery owner from northwestern Oklahoma. After earning an MFA from the University of Iowa in 1943, he taught art at several universities before returning to Bannister Ranch in Arnett, Oklahoma. Eventually moving to Amarillo, Texas, in 1953, he opened the Dord Fitz School of Art and the Dord Fitz Gallery. Enamored with modern art after meeting the Abstract expressionist painter Milton Resnick in 1957, Fitz began organizing exhibitions of works by some of the leading Ab-Ex painters from New York in Amarillo. His best-known shows included works by Elaine de Kooning, Louise Nevelson, and Jeanne Reynal. He also organized trips to NYC to visit artists’ studios for his local students. Reynal visited Amarillo several times, and while her husband, painter Thomas Sills, did not, he did send his work for inclusion in the exhibitions held there. His New York studio was also a destination for the Amarillo students.

It was through this exchange that significant collections of work by Reynal, Sills, de Kooning, Nevelson and other important artists ended up in Amarillo. The Sills painting, Red Dream, comes from one of these collections.

Thomas Sills

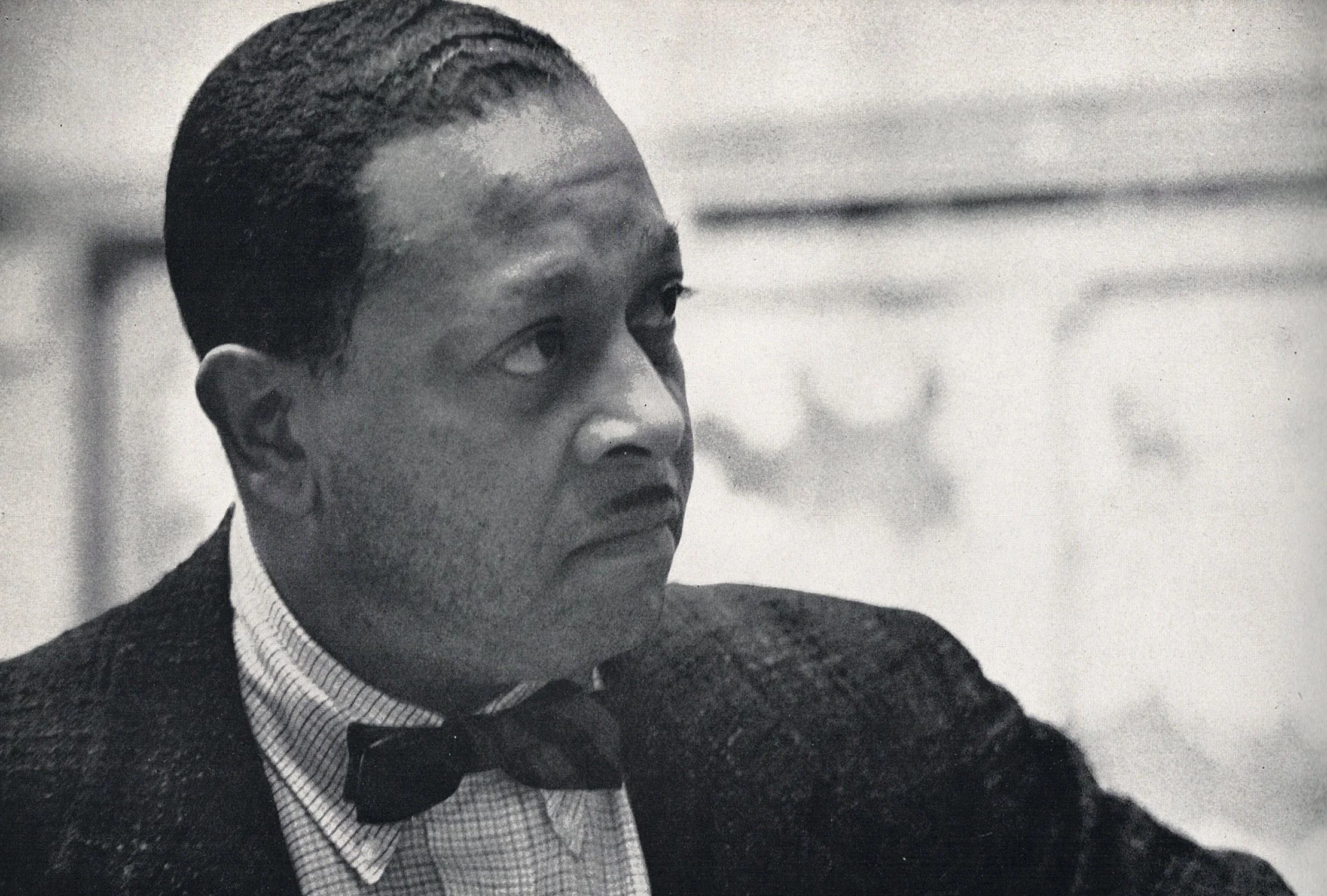

Artist Thomas Sills speaking about his process in the 1973 film Black Artists in America, v. 3 which was produced by Dr. Oakley N. Holmes.

Thomas Albert Sills was born in Castalia, North Carolina in 1914 to sharecroppers Baldie Sills and Cynthia Selton Sills. He had ten siblings, nine brothers and two sisters, and by the time he was born his eldest brother was more than 30 years old. He went to work at a greenhouse in Raleigh, NC, when he was only nine years old. He moved to Brooklyn to live with one of his brothers at the age of 11. He held jobs as a doorman and in the cleaning and pressing business, and in 1940, he met and married Elsie Reid. The couple had two children, but they divorced within a few years and Sills returned to Raleigh. In 1948, he returned to New York, and this time, it was for good. He met his second wife, Jeanne Reynal, while working as a stevedore and at a well known liquor store.

Reynal was a surrealist artist known for her work in mosaics. Through his wife, he met painters Willem de Kooning, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Arshile Gorky, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Sills began painting in 1953, the year they were married. In their home, he was surrounded by works by these artists, which influenced his own artistic endeavors. Encouraged especially by his wife and de Kooning, he began creating paintings, forgoing the use of brushes and applying paint with rags. By 1955, he had scored a one-person exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery. Lawrence Campbell, an important art critic and author of Sills, says, “To show at the Betty Parsons Gallery the artist must be, not seem, original.” (1)

In 1957 he won the prestigious William and Noma Copley Foundation Award and held solo exhibitions at the Betty Parsons Gallery, NY; Paul Kantor Gallery, CA; and Bodley Gallery, NY. His work was also included in many group exhibitions including the Fourth Annual Artists Annual at Stable Gallery, NY. The Stable Gallery was the center of Abstract Expressionism in New York City in the 1950’s and home to artists Robert Indiana, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol, and Lee Krasner.

After his first show at Parsons (he had four between 1955-1961), Sills’ approach was affected by his reading of John D. Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art, written in 1937. The influence was less about his stylistic concerns and more about his overall feeling about painting itself. “Graham argued that because art was essentially abstraction, it dealt not with subject matter but with psychological problems of form. Thus, he argued that artists should not portray life or nature but use them as a point of departure to reveal truth. He saw painting as the articulation of space, and therefore every move made by the painter should be fatal, determining the infallible position of shapes relative to each other and to the whole.” (2)

“Before 1968, Sills’ reputation was based on his work alone and not on his ethnicity. He was not presented or discussed as a Black artist. This is unsurprising given that he created his paintings in response to methods and concepts in abstract painting rather than to autobiographical narrative. However, in 1968, he began to be included in exhibitions of African American art, organized in response to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, in the realization that Black artists had often been overlooked and that their work was frequently omitted from important group exhibitions and serious art criticism. “ (3)

Sills work was included in some significant exhibitions at that time, such as Contemporary Black Artists (Minneapolis institute of Arts ),1968; and Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston, (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1970. In the Greenville Museum of Art’s catalog, Thomas Sills, Man of Color, Lisa N. Peters points to Sills being quoted in Elsa Honig Fine’s 1973 book, The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity.

“I hate to be classed as a black painter. I figure I am a painter. Take five of my words and mix them up with a lot of other people’s and I say, “You pick out the black painter.” Black artist! You know, once you get labeled, it’s hard as the devil to get it off. But guys still keep working and that’s the only thing. You got to walk in that studio and close the door and say, ‘Now I’m the boss.’ (4)”

Sills, Thomas, and Lawrence Campbell. Sills. William and Noma Copley Foundation, 1963.

Peters, Lisa N. “Thomas Sills.” Thomas Sills: Man of Color, Greenville County Museum of Art, 2021, pp. 9–25.

ibid, p. 20

ibid, p. 21